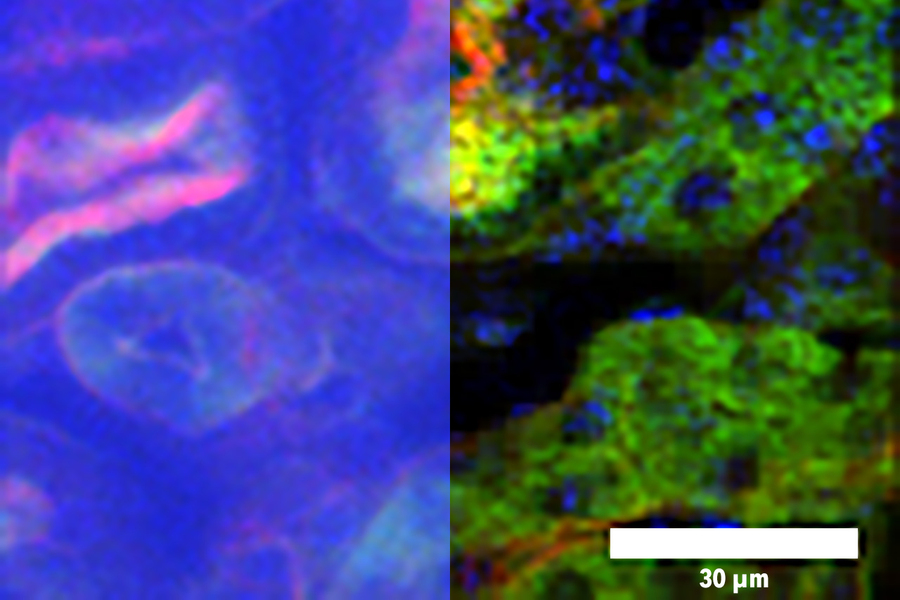

Researchers could rapidly obtain high-resolution images of blood vessels and neurons within the brain.

[ Source: MIT News Office ]

To create high-resolution, 3D images of tissues such as the brain, researchers often use two-photon microscopy, which involves aiming a high-intensity laser at the specimen to induce fluorescence excitation. However, scanning deep within the brain can be difficult because light scatters off of tissues as it goes deeper, making images blurry.

Two-photon imaging is also time-consuming, as it usually requires scanning individual pixels one at a time. A team of MIT and Harvard University researchers has now developed a modified version of two-photon imaging that can image deeper within tissue and perform the imaging much more quickly than what was previously possible.

This kind of imaging could allow scientists to more rapidly obtain high-resolution images of structures such as blood vessels and individual neurons within the brain, the researchers say.

“By modifying the laser beam coming into the tissue, we showed that we can go deeper and we can do finer imaging than the previous techniques,” says Murat Yildirim, an MIT research scientist and one of the authors of the new study.

MIT graduate student Cheng Zheng and former postdoc Jong Kang Park are the lead authors of the paper, which appears today in Science Advances. Dushan N. Wadduwage, a former MIT postdoc who is now a John Harvard Distinguished Science Fellow in Imaging at the Center for Advanced Imaging at Harvard University, is the paper’s senior author. Other authors include Josiah Boivin, an MIT postdoc; Yi Xue, a former MIT graduate student; Mriganka Sur, the Newton Professor of Neuroscience at MIT; and Peter So, an MIT professor of mechanical engineering and of biological engineering.

Deep imaging

Two-photon microscopy works by shining an intense beam of near-infrared light onto a single point within a sample, inducing simultaneous absorption of two photons at the focal point, where the intensity is the highest. This long-wavelength, low-energy light can penetrate deeper into tissue without damaging it, allowing for imaging below the surface.

However, two-photon excitation generates images by fluorescence, and the fluorescent signal is in the visible spectral region. When imaging deeper into tissue samples, the fluorescent light scatters more and the image becomes blurry. Imaging many layers of tissue is also very time-consuming. Using wide-field imaging, in which an entire plane of tissue is illuminated at once, can speed up the process, but the resolution of this approach is not as great as that of point-by-point scanning.

The MIT team wanted to develop a method that would allow them to image a large tissue sample all at once, while still maintaining the high resolution of point-by-point scanning. To achieve that, they came up with a way to manipulate the light that they shine onto the sample. They use a form of wide-field microscopy, shining a plane of light onto the tissue, but modify the amplitude of the light so that they can turn each pixel on or off at different times. Some pixels are lit up while nearby pixels remain dark, and this predesigned pattern can be detected in the light scattered by the tissue.

“We can turn each pixel on or off by this kind of modulation,” Zheng says. “If we turn off some of the spots, that creates space around each pixel, so now we can know what is happening in each of the individual spots.”

After the researchers obtain the raw images, they reconstruct each pixel using a computer algorithm that they created.

“We control the shape of the light and we get the response from the tissue. From these responses, we try to resolve what kind of scattering the tissue has. As we do the reconstructions from our raw images, we can get a lot of information that you cannot see in the raw images,” Yildirim says.

Using this technique, the researchers showed that they could image about 200 microns deep into slices of muscle and kidney tissue, and about 300 microns into the brains of mice. That is about twice as deep as was possible without this patterned excitation and computational reconstruction, Yildirim says. The technique can also generate images about 100 to 1,000 times faster than conventional two-photon microscopy.